The Church in Ireland in the 12th century was radically changed by a number of reforms. Among the abuses that existed was that whereby the hereditary secularised ecclesiastical dynasty of the Clann Sínaigh had asserted monopoly of clerical office at Armagh for almost 200 years. Two key figures in this reform were Ceallach (St Celsus) comharba Phádraig (1105-1129) and Maolmhaodhóg Ua Morgair (St Malachy).

The turning point for the Armagh reform was the emergence of the reformer Ceallach who belonged to the usurpers, the Clann Sínaigh. Ceallach, Abbot at the Armagh Abbey, took the first step towards canonical correctness by being ordained priest and bishop.

Maolmhaodhóg, whose birthplace in Armagh city is marked by a plaque, was educated by Imhar who was later to become Abbot of the newly founded Abbey of SS Peter and Paul. Ceallach groomed the talented student by ordaining him five years younger than was the norm then and had him act as his vicar during Ceallach’s absence. Malachy was trained for a short period in Lismore monastery which had close links with Britain and the continent and thus with the on-going reform movement in Europe initiated by Pope Gregory VII (1073-85).

Malachy was appointed bishop of Down and Connor in 1124 and as Abbot undertook the rebuilding of the illustrious abbey of Bangor. As bishop he began a programme of reform but met with such opposition that he was forced to flee with his monks to Munster.

Before he died in 1129 Ceallach requested that Malachy should be his successor and sent him his crozier. Earlier, having taken the first step to break the hereditary succession of the coarbs of Armagh from within the Clann Sínaigh this singling out a successor outside the family hegemony dealt a death blow to the Clann Sínaigh.

Malachy hesitated to accept the onerous responsibility but after 3 years, on the insistence of the papal legate, Bishop Gilbert of Limerick, and of the bishop of Lismore accepted the appointment. Even so he faced great opposition from the traditionalists in Armagh who elected Muircheartach of the Clann Sínaigh, lay abbot and coarb to succeed Ceallach. Malachy did not return to Armagh until after Muircheartach’s death in 1134 when the support of Cinél Eoghain ensured his superiority over Niall of the Clann Sínaigh as Muircheartach’s successor. With peace now restored and the reform assured Malachy appointed as his own successor in Armagh, Gilla Mac Líag, abbot of Derry, member of the Cinél Eoghain and a reformer to boot.

In the interest of his reform movement Malachy transferred the territory of the present-day Co. Louth, which was then part of Ua Cearbhall’s Kingdom of Aírghialla, to the diocese of Clogher and appointed his own brother, Gilla Críst, bishop. For the next 60 years the bishops of Clogher styled themselves bishops of Louth. The diocesan See was moved from Clogher to St Mary’s Abbey at Louth and its Augustinian Canons formed the cathedral chapter. In this rather drastic alienation of diocesan territory Malachy was recognising a political fact as well as winning the support of the warrior king, Donnchadh Ua Cearbhaill.

Having returned to Bangor Malachy decided to separate the dioceses of Down and Connor and had another bishop ordained for Connor but himself retained Down. His first act on returning to his former diocese was to re-establish the abbey at Bangor and set about a reform of the community where his earlier reforms came to an abrupt end and led to his flight to Munster.

Though he was no longer bishop of Armagh Malachy was accepted as leader of the reform movement and travelled throughout the country promoting church reform. He realised that his hand would be strengthened considerably in his cherished reforms if the new diocesan arrangements made by the national synod of Rath Breasail in 1111 which decreed there be two archbishoprics for the country – one at Cashel for the southern part of the country and the other at Armagh – were to receive the official recognition and backing of Rome. This would entail travelling to Rome and formally requesting the pallia.

Setting out late 1139 or early 1140 Malachy and his entourage visited the Cistercian abbey at Clairvaux where he first met the abbot, St Bernard. They became firm friends and Malachy was greatly enamoured with the Cistercian way of life. Pope Innocent II received him graciously in Rome but refused to grant him permission to spend the remainder of his life at Clairvaux. Instead, Innocent appointed him successor to Gilbert, the papal legate for Ireland, confirmed the status of Cashel as an archbishopric but did not confer the pallia on either Armagh or Cashel, but urged that a national synod be held to formally petition the pallia.

On his return journey Malachy and his party called again at Clairvaux and left four of his retinue there to be trained as Cistercians. On his return to Ireland he sent others to Clairvaux. From these two groups, with the addition of Clairvaux monks, Mellifont Abbey near Drogheda was founded in 1142. Malachy also visited the monastery at Arrouaise in Flanders whence he introduced the Augustinian Canons into Ireland at St Mary’s Abbey, Louth, also in 1142. Both Mellifont and Louth Abbey were situated in the Kingdom of Airghialla, the protection and patronage of whose king, Donnchadh Ua Cearbhaill, enabled Malachy to introduce these continental monastic observances.

As papal legate he spent the next six years holding synods, making new church laws and generally renewing the life of the Church in Ireland. In 1145 a former Clairvaux monk was elected Pope – Eugene III – and Malachy thought it was now opportune for him to again request the pallia. In 1148, availing of the fact that the Pope had summoned a church council at Reims, Malachy undertook a second journey to the continent, having first convened a synod near Skerries for the purpose of making a formal request for the pallia.

On his journey to France he was prevented, by King Stephen of England, from crossing the English Channel immediately because of the latter’s dispute with the papacy and by the time he reached France the Pope was on his way back to Rome. Malachy now decided to visit St Bernard at Clairvaux again, arriving there mid-October. A few days later he was prostrated with a fever but the monks were not unduly alarmed even though Malachy insisted he was on his death-bed and asked for the last rites. He became suddenly critically ill on All Saints Day and in the presence of the assembled community and, in the arms of St Bernard, died on All Souls Day, 1148.

The monks of Clairvaux initiated proceedings for his canonisation, which Pope Clement III confirmed in 1190. St Bernard’s biography of Malachy, as well as letters written to him during his lifetime, are the most important sources for his life.

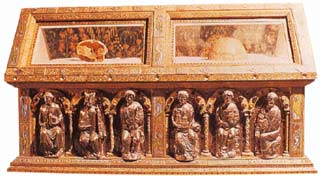

The bones of St Malachy remained in France until in 1982 for the most recent renovation of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Armagh, the return of a portion of his remains was negotiated and part of which was placed in the new altar during the ceremony of re-dedication. And so the mortal remains of two of Armagh’s most celebrated archbishops to follow Patrick, one of whom, Malachy, guided the Church in Ireland through the tensions of reform and the other, Oliver Plunkett, through the rigours of persecution, to the scene of their labours for peace in Armagh.

St Malachy’s feast day is celebrated on All Souls Day.

Dermot McDermott, CFC.

You must be logged in to post a comment.