The death has taken place on Wednesday 8 November 2023, of Fr Brian White, Tullysaran, Armagh.

May he rest in peace.

Archbishop Eamon extends the sympathy of Cardinal Seán, Bishop Michael, the clergy and the people of the Archdiocese to Fr Brian’s family.

CURRICULUM VITAE

Rev Brian White

Born: 6 February 1977, Parish of Armagh

Studied: St Patrick’s Grammar School, Armagh 1988 – 1995

Queen’s University Belfast 1995 – 1998

St Patrick’s College, Maynooth 1998 – 2003

Ordained: 29 June 2003, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Armagh

Appointments

Curate, Drumcree 2003 – 10

Curate, Haggardstown & Blackrock 2010 – 19

Assistant Priest, Keady & Derrynoose 2019 – 20

Chairperson, Armagh Diocesan Youth Council 2007 – 16

Director of Formation, Permanent Diaconate 2016 – 20

Since 2020, during a time of ill health, Fr White provided assistance to the parishes of Dungannon, Warrenpoint & Burren (Dromore Diocese), and parishes in Dundalk.

Date of Death: 8 November 2023 at his home in Tullysaran, Armagh

Davis Haberkorn was born in Colorado (USA) in 1991. He is the second child of Dennis and Sandra, along with his sister Kira and his brother Anthony. Before beginning his formation, he was working as a mechanical engineer. He started his formation to the priesthood in the Redemptoris Mater Seminary in Dundalk in the year 2015.

Davis Haberkorn was born in Colorado (USA) in 1991. He is the second child of Dennis and Sandra, along with his sister Kira and his brother Anthony. Before beginning his formation, he was working as a mechanical engineer. He started his formation to the priesthood in the Redemptoris Mater Seminary in Dundalk in the year 2015. Francesco Campiello was born in Vicenza (Italy) in 1993. He is the second child of Diego and Paola. He has other four brothers and four sisters. He started his formation to the priesthood in the Redemptoris Mater Seminary in Dundalk in the year 2014.

Francesco Campiello was born in Vicenza (Italy) in 1993. He is the second child of Diego and Paola. He has other four brothers and four sisters. He started his formation to the priesthood in the Redemptoris Mater Seminary in Dundalk in the year 2014.

The Festival of Families: A Celebration of Unity

The Festival of Families: A Celebration of Unity Pope Francis Pilgrimage to Knock: A Journey of Faith

Pope Francis Pilgrimage to Knock: A Journey of Faith The Papal Mass: A Gathering of Hearts and Souls

The Papal Mass: A Gathering of Hearts and Souls

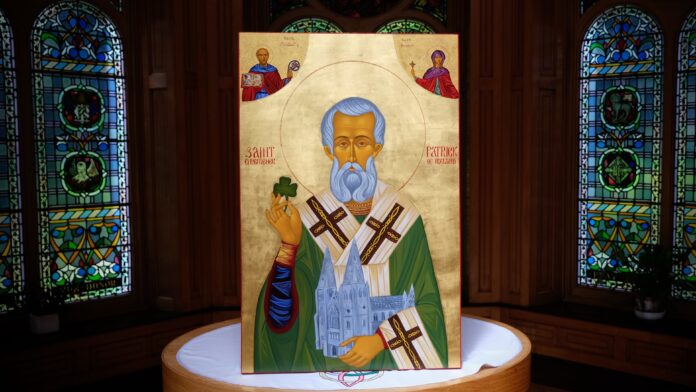

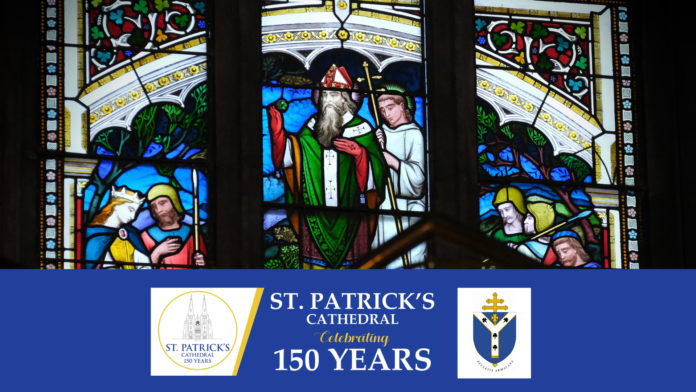

Today in the Archdiocese of Armagh, we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the first dedication of St Patrick’s Cathedral which took place on 24 August 1873.

Today in the Archdiocese of Armagh, we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the first dedication of St Patrick’s Cathedral which took place on 24 August 1873.