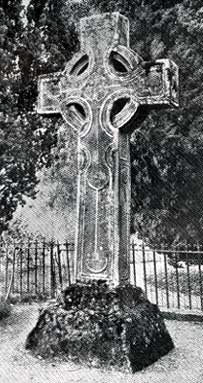

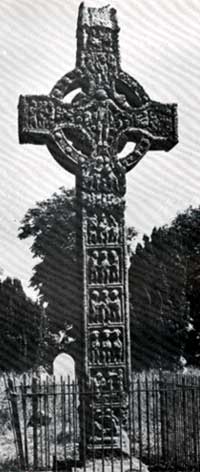

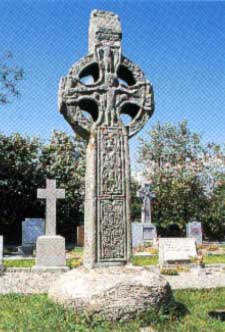

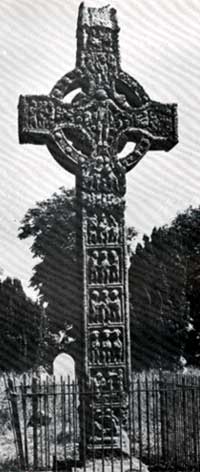

There are three High Crosses located in the churchyard, Monasterboice, Co. Louth. The best known of these is the South Cross or, as it is commonly called, Muiredach’s Cross, so described on account of the inscription which appears on one side of the shaft which reads: OR DO MUIREDACH LASNDERNAD IN CHROS (A prayer for Muiredach for whom the cross was made). The Muiredach referred to is believed to be Muiredach, son of Domhnall, a cleric of considerable importance and abbot of Monasterboice who died in 922. Consequently the monument is regarded as dating from the early tenth century.

The Cross stands about seventeen feet high and consists of a truncated pyramidal base from which rises a shaft surmounted by a large ring-head, on which the billet mouldings are not placed on the arcs of the ring, but on the rounded angles of the intersections of the arms on the shaft. The cross is finished by a roof-shaped cap; this is represented on each wide side of the shaft by panels of shingling topped by a massive roof-tree, while on the two narrow sides the heavy gables rise to form crescentic or horned finials decorated by pellets.

|

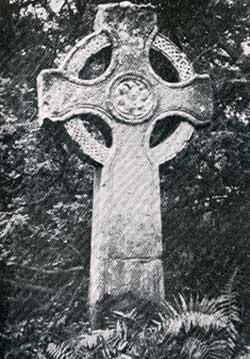

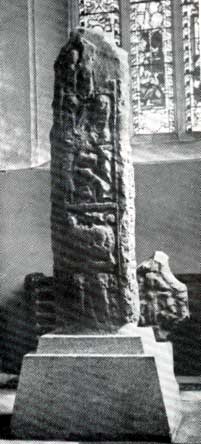

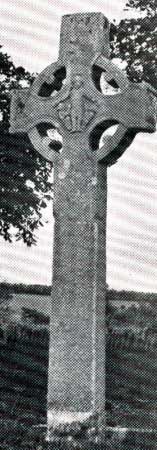

The West or Tall Cross is about twenty-one feet high. This monument consists of a truncated pyramidal base from which the shaft, surmounted by a ring-head, rises. As on Muiredach’s Cross the billet mouldings are placed, not on the arcs of the ring, but on the rounded angles of the intersection of the arms. The cap is roof-shaped and the shingles of the roofing appear on all four sides of the cap.

|

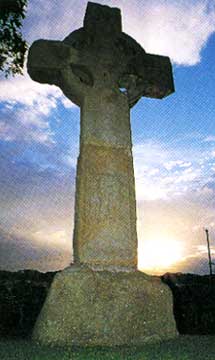

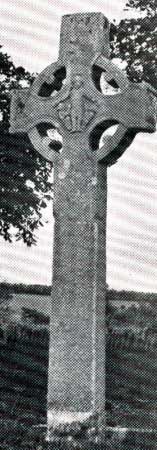

Of this cross, which stands about sixteen feet high, only the head and upper part of the shaft are original. The cross-head is well proportioned and surrounded by a ring with a billet or roll on each arc. The angles of the arms and shaft are rounded and double incised lines delimit the field of the cross-head. There is a rectangular panel framed by an incised line at the end of each arm. There is no cap.

|

|

Abstracted from Seanchas Ardmhacha, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1954) p. 102-109