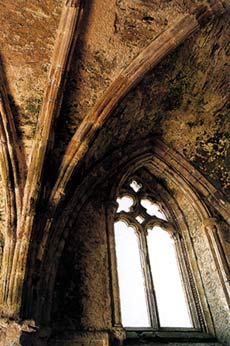

Chapter House, Mellifont

Bernard of Clairvaux was the most remarkable figure of his century in Europe. He was a great Cistercian monk, a man of prayer, a great spiritual writer and a gifted preacher. He was the trusted advisor to Popes and kings. In a Church split between the rival claimants to the papacy, his advice was sought and followed. One of his monks from Clairvaux was elected Pope, Eugenius III. Foundations from Clairvaux became numerous and Mellifont Abbey, the first Cistercian Abbey in Ireland, was to be one of these.

The Founding of Mellifont Abbey

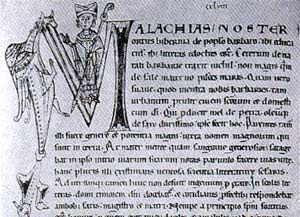

In 1140 Maelmhadhog O’Morgair, better known as St. Malachy, the great reforming bishop of Down and at one time Archbishop of Armagh was travelling to Rome. Attracted by the fame of St. Bernard he visited Clairvaux and was so impressed that on arriving at Rome he petitioned the Pope’s permission to resign his bishopric and enter Clairvaux as a novice. This permission was refused but on his return journey he left some of his companions at Clairvaux to be trained in Cistercian life with a view to founding a monastery of the Order in Ireland.

St. Malachy chose a site for his proposed monastery five miles north of Drogheda in Co. Louth. This land was in the territory of Donnachadh Ua Cearbhaill, king of Airghialla who donated not only the land but also the materials for the building of the new abbey. The first group of monks, the Irishmen trained by St. Bernard at Clairvaux, accompanied by some French monks who were to direct the building of the new abbey, arrived in 1142. Initial difficulties arising from the French design of the abbey, which interrupted the work, were settled by St. Bernard and St. Malachy and the construction was resumed and continued until completion in 1157. Before that date, however, St. Malachy again called at Clairvaux on another journey to Rome in 1148. While there he was struck down by fever and died in the arms of St. Bernard on 2nd November.

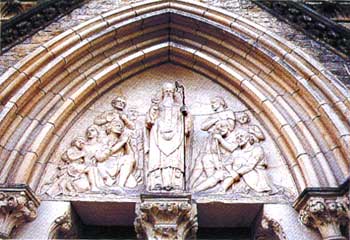

One of the young men left by St. Malachy with St. Bernard at Clairvaux was Gillacrist (Christian). He became the first abbot of the new monastery but in 1150 Pope Eugenius, his former fellow-novice at Clairvaux, appointed him Bishop of Lismore and Legate of the Holy See to Ireland. In this capacity he attended the consecration of the new abbey church in 1157. The consecration was performed by the Archbishop of Armagh in the presence of seventeen other bishops, the High King of Ireland and many local kings and chieftains.

Mellifont’s Filiations

Within eleven years of its own foundation, Mellifont founded seven daughter houses. It was later to found an eighth. These abbeys, in their turn, sent out new foundations which brought the total number of monasteries tracing their filiation through Mellifont to 28. The great Irish monastic tradition had burst into flower again; the future looked bright indeed.

The Norman Invasion

Within thirty years of the founding of Mellifont an army landed on the Wexford coast in 1169. The Norman invasion of Ireland had begun. The Normans were not opposed to Cistercian monastic life and as they advanced they confirmed the existing abbeys in their titles to their properties. They, themselves, founded new Cistercian abbeys, bringing communities from England and Wales to occupy them. As time passed, however, they sought to use the monasteries as centres of Norman influence by having Norman monks appointed to all positions of authority in them and, in some cases, expelling Irish monks and replacing them by men brought in from foreign monasteries.

When he set to revitalise Irish monastic life, St. Malachy had chosen the Cistercian Order, which through its system of Visitations and General Chapters would gradually correct any weaknesses of observance. This corrective process was part of the normal development of any new community in the Order, and was accepted as such. After the invasion of Ireland the abbots appointed as Visitors to the Irish monasteries were themselves Normans. Their visitations, which were intended to promote observance of the Rules of the Order and peace and harmony in the communities, were perceived by the Irish communities as Norman attempts to undermine and replace native Irish superiors. The disastrous results of this perception were predictable. It is impossible now to form an accurate judgement on the situation in the Irish monasteries as all available records are from Norman sources and we do not have balancing records from the native Irish viewpoint. Norman influence at the General Chapter of the Order reached a climax in 1227 when it deprived Mellifont of its jurisdiction over its filiations and transferred it to abbeys in England and Wales. Only gradually did the General Chapter become aware of the true situation. In 1274 it condemned the laws being enforced under Norman control, forbidding the reception of native Irish novices or the appointment of Irish monks to any position of authority in their communities. Finally it reversed its earlier decision and returned to Mellifont its jurisdiction over its filiations. The following thirty years brought a succession of Irish abbots to Mellifont and a return to its recognition by the General Chapter as the leading abbey of the Order in Ireland. It was a period of hope.

Sadly the hope was again stifled by political pressure. The civil powers ignored the General Chapter’s condemnation of Anglo Norman discrimination, and by the end of the 14th century Mellifont had become a recognised Anglo Norman institution. As such, it was treated with favour by the reigning English monarch who conferred on it many civil privileges and further large tracts of land. At the beginning of the 15th century, Mellifont Abbey had become the proprietor of estates totalling 48,000 acres. The abbot had become a great feudal lord exercising civil, as well as, ecclesiastical jurisdiction in his domains and having a seat in the English House of Lords. As a totally English establishment, Mellifont had naturally lost all contact with and control over its filiations in Irish ruled territories. As its worldly prestige increased it declined as a spiritual force and the number of its monks diminished. The Lay Brothers, who had formed so important a part of the early Mellifont community, gradually disappeared altogether. The Cistercian ideal, which had so inspired St. Malachy – a community of monks living a simple prayerful life and rejecting all sources of income apart from the labour of their hands – was forgotten. Mellifont’s community had become landlords, living on the revenues of their huge estates and from the parishes, churches and chapels under their jurisdiction.

The Black Death which decimated the population of Europe and the Great Schism of 1374-1417 which split Western Christendom, both left their mark on the Irish Church. The divisions arising from the latter, and rivalries within the Order itself at this period, weakened the authority of the General Chapter as an agent for reform. Nevertheless, many reform movements were attempted in the Order as a whole and in the Irish monasteries but with little success. It can be said that, under both Irish and Norman abbots, the life of the Mellifont community was regarded, in the context of its times, as exemplary. Mellifont and St. Mary’s Abbey in Dublin were the two communities where the Choral Office was religiously carried out to the very end. There were relatively short periods of bitter strife in the community’s long history, when a deeply religious life would have been extremely difficult; these were invariably caused by forces outside the community. The two Abbeys, Mellifont and St. Mary’s were in the final period of their history at the forefront of every movement towards reform in the Irish monasteries. But the hope of recovery from the consequences of that fateful day in 1169, when a band of soldiers landed on the coast of Wexford, was finally shattered in 1539 by the decision of King Henry VIII of England to suppress all the monasteries in his realm and to divide their possessions among his political supporters.

The earthly ruins of the work of 400 years stand silently today on the banks of the little River Mattock, but the voices that sang the praises of God in the old stone church continue that song today around the throne of God. The real work of the monastery continues into eternity. In 1938 a new band of Cistercian monks from Mount Melleray Abbey Co. Waterford returned to the old monastery lands, 3.5 miles away in Collon, to take up again the singing of God’s praises interrupted in 1539.

Visiting the Ruins Of Mellifont Abbey today

On approaching the ruins of Mellifont Abbey today, the first building that the visitor encounters is a massive, castle-like structure with a turret at its north east corner. This is all that remains of the original gate house of the old abbey. The entrance road formerly led through the archway beneath the tower. This great defensive structure, three storeys high above the vaulted basement was a necessity in the centuries when Mellifont stood on the border between the “Pale” (that part of Ireland under Anglo-Norman rule) and the territory under the control of the native Irish chieftains. The tower was strategically sited on a projection of naked rock within a few yards of the river The area around this guesthouse was occupied by a variety of buildings: the abbot’s residence, the guesthouse, the hospice for the poor, etc. All of these have disappeared completely. In 1826 a flour mill was built to the south of this gate house and the old road running under the arch was used as the channel for a mill race. This mill which had been disused for many years has since been demolished.

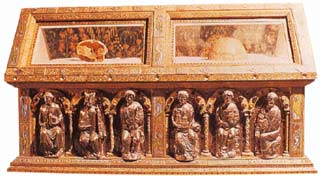

Arriving at the present entrance gate to the abbey ruins the visitor can look down on the outline of the entire abbey buildings below. As Mellifont was originally built by monks sent from Clairvaux by St. Bernard, its plan follows closely that of its mother house. Along the northern side, nearest to the entrance gate, the great abbey church, 190 ft long x 54 ft wide, including the side aisles, ran from east to west. Beyond the church stretched a rectangular open space – the cloister garth, which was surrounded on its four sides by the cloister, a covered passage linking all the main buildings of the abbey. On the east side of the cloister stands the chapter house, where meetings of the community were held. Its vaulted ceiling is still intact but its once elaborately decorated entrance arch has been removed. Rooms, such as the bursar’s office and store rooms, occupied the remainder of this side of the cloister and the upper storey of this wing was the choir monks dormitory. Opening unto the south cloister were the refectory (community dining hall), kitchen, warming room, etc. Four of the arches of the octagonal “Lavabo”, which once housed a central fountain for hand washing before meals, still stand in the cloister garth opposite the entrance to the refectory. On the west side of the cloister are the foundations of the lay brothers quarters.

Excavations have revealed a constant tendency to expansion and renovation over the four centuries during which the Cistercians occupied the abbey. The presbytery and transepts of the Church were completely remodelled in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and a new chapter house, the one which we can see today, was built at the same period.

The Years Between

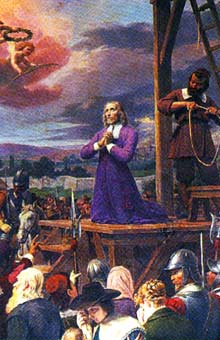

Historians find no evidence for the local tradition that there existed from the time of the suppression of Mellifont down to the Cromwellian conquest, a community deriving an unbroken continuity from that of the suppressed abbey, and which ministered to the faithful in the district. The first of these Fr. Candidus Furlong was appointed in 1609, 70 years after the suppression. Another, appointed in 1620, did gather a little Cistercian community in Drogheda, two members of which were martyred during the Cromwellian regime.

After the suppression of Mellifont Abbey in 1539 by King Henry VIII, the abbey and its lands came into the hands, successively, of the Townley, Brabazon, and Moore families. Sir Garrett Moore, who lived at the abbey in 1603, was a close friend of Hugh O’Neill, and it was to Mellifont that Hugh O’Neill came to make his submission to the Lord Deputy Mountjoy at the end of the Nine Years War. He returned to Mellifont to bid farewell to his friend before setting out on his last voyage, which was to become known in history as the “Flight of the Earls”. Garrett Moore, Viscount of Drogheda, died in 1628. His son Charles succeeded him but was killed in an engagement with Owen Roe O’Neill in 1643. Henry Moore, his successor, entertained the officers of King William at Mellifont on the night before the battle of the Boyne. In 1927 the fifth Earl of Drogheda sold Mellifont Abbey and its surrounding lands to Mr. Balfour of Townley Hall, and he himself settled permanently at the monastery of Monasterevan, which the Moore family had acquired through marriage, renaming it “Moore Abbey”. Two years later he sold another parcel of the estate, including the greater part of the townland of Collon. This eventually passed into the hands of the Foster family, an English family who had settled at Dunleer. The village and its surroundings which had prospered as part of the estates of Mellifont Abbey before its suppression, had, at this period, become derelict and very sparsely inhabited. Anthony Foster set about remedying this situation by bringing in fifty French and English Protestant families, and investing huge sums of money in land improvements. His son John, born in 1740, married in 1764. His wife became Baroness Oriel, and later Viscountess Ferrard in 1797. John was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1785 and Speaker of the House of Commons from 1785 until the abolition of the Irish Parliament by the Act of Union in 1800. He was the strongest opponent of the Act of Union and in 1826 equally strongly opposed Catholic Emancipation. He died aged 88 in 1828. In l810, John’s second son married Harriet Skeffington, assuming the Skeffington name, in order to inherit the Skeffington estates in Co. Antrim. In 1911 Viscount Masserene moved to Antrim Castle, leasing Oriel Demesne to a Mrs. Daly. It was later purchased by James Lyons, who sold the growing timber on the demesne to a sawmiller David Rea. The demesne and residence was eventually sold to Thomas Alexander Rudd who fought, and won, a protracted law case with Rea. When Mr. Rudd died in 1936 the estate passed into the hands of the Land Commission and in 1938 was purchased by the Cistercian community of Mount Mellery.